Can the Creativity Of A Cut Be Measured? & How Big Data Will Change Filmmaking

Watch The Presentation at the LA Creative Pro User's Group

Typically when I tell people that EditStock sells unedited films to practice editing they think of EditStock as a stock footage website. But we’re not. At our core we are an education company. My background is in editing of course, but also in teaching editing.

After years of watching the same scene cut over and over again what I’ve come to realize that the way we train editors all wrong. And it's about to change in a big way - a big data way that is. First, let’s discuss what I mean by big data.

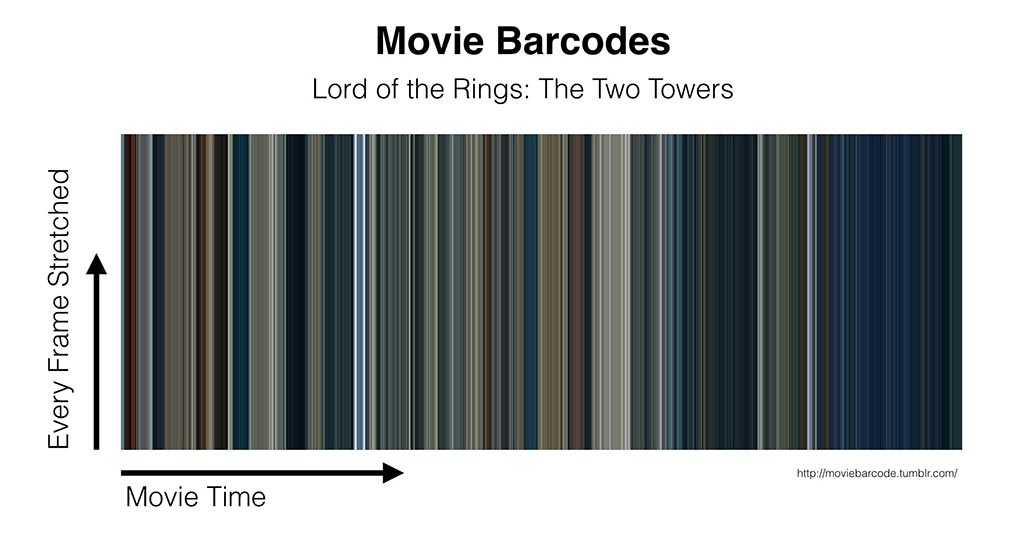

Movie Barcodes

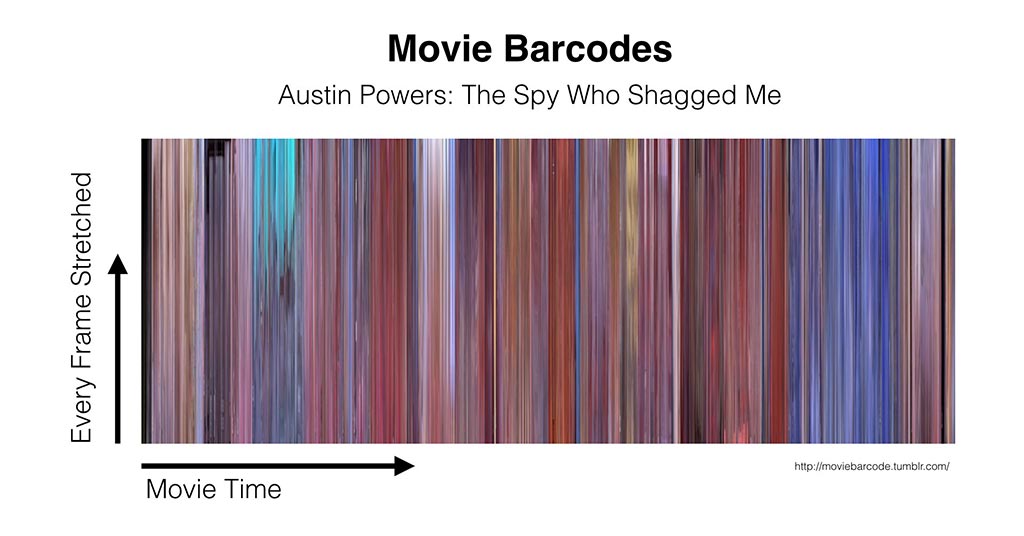

This image is from the movie Austin Powers, The Spy Who Shagged Me. I found it on an anonymous tumbler blog called Movie Barcode. Let me correct myself a bit here, this image is not from the movie Austin Powers, but rather it is the whole movie, represented in a graph.

What movie barcodes do is take every frame of picture and stretch it out vertically to fill the chart. As we move left to right along the chart we’re looking at the runtime of the movie. The closer the horizontal bands are together the longer the movie. Vertically we’re not looking at data of any particular statistical value or importance. Vertically we’re literally just taking the picture and stretching it out and making a fun design in the process. Let me show you a few more movie barcodes, because they are really fun to look at.

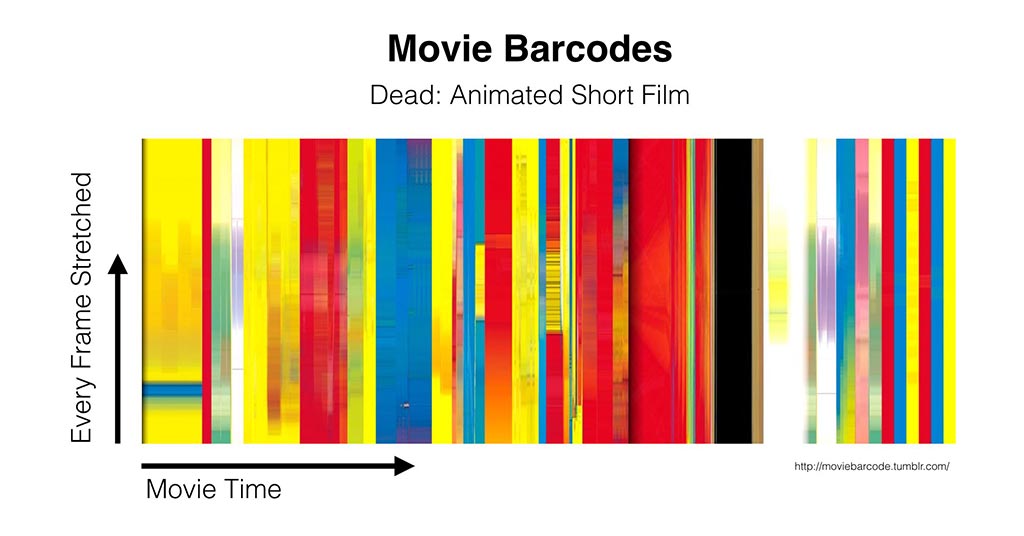

This is a barcode from an animated short film called Dead. Notice how much wider the horizontal bars are? That’s because the movie is only four minutes long, and the width of the movie barcode is always the same. A two hour movie is six inches wide, as is a four minute movie (slide).

Comparing Movie Barcodes

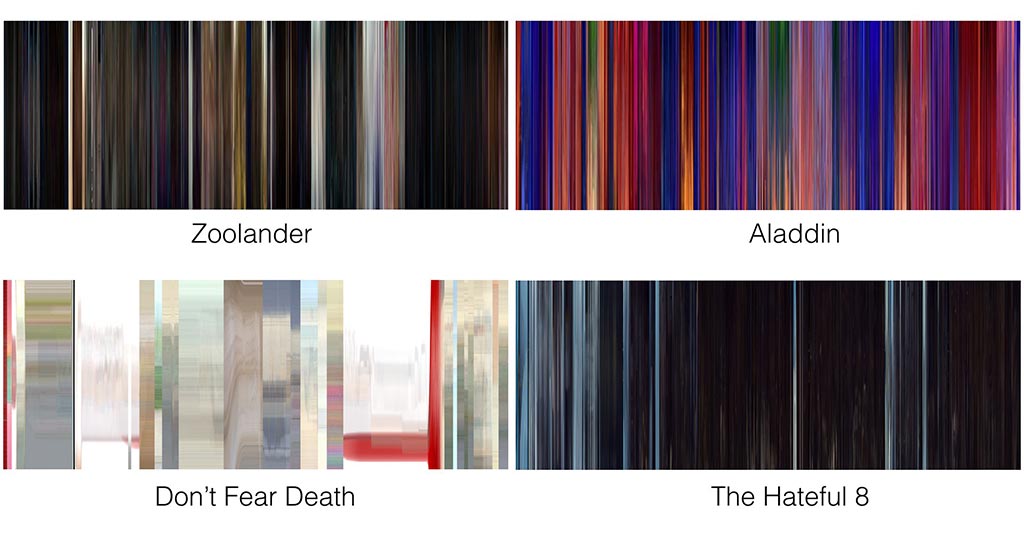

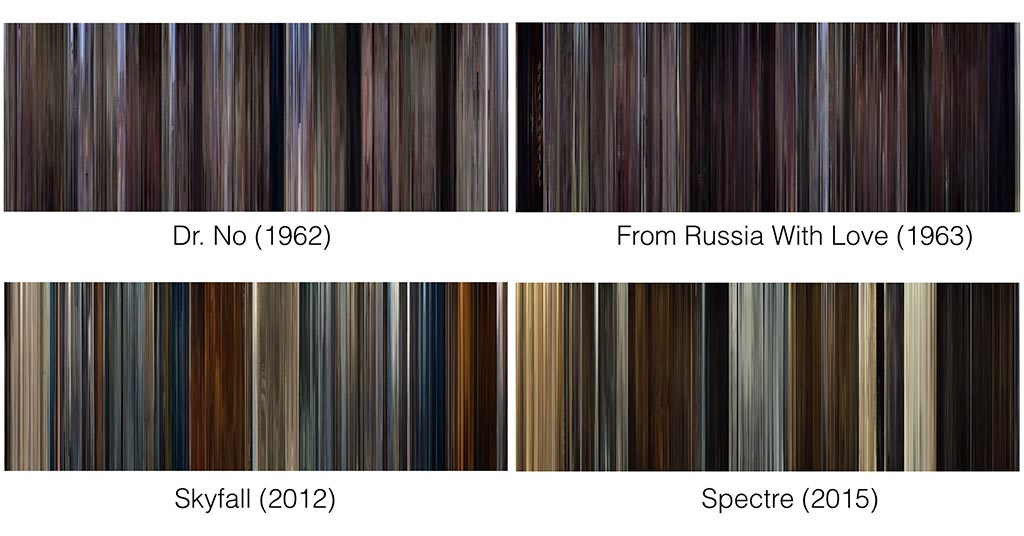

When we place movie barcodes from different movies side by side we gain a really fun new perspective on filmmaking. We start to compare movie color pallets for example. I included Don’t Fear Death on here because I thought the barcode looked cool. Don’t Fear Death is a three minute animated short film.

Next, and this will be fun for all you James Bond lovers out their like myself, these are movie barcodes from four James Bond films - two older ones from the 60’s and two from this decade. Movie barcodes make it fun to compare color pallets used across generations of Bond films. Does Bond have a look? Is there a theme?

What's the Point Of A Movie Barcode?

Finally, this is one of my favorite movies, the Lord of the Rings; The Two Towers represented in all its glory as pin stripes. What do we want to do with this information?

I want someone out there reading this to buy me these awesome LOTR throw pillows! Seriously though, what these graphs do? I mean they collect data and organize it I guess, and that’s lucky for me because it’s the main theme of this blog post, but what is the point of having them otherwise? What is the point of this data?

What Film Data Is

Data is noise. Data is thoughtless. Data is literally just a measurement, but those measurements can be of anything, and more and more mankind is measuring everything.

The purpose of having a massive data collection is figuring out what it means. What’s the message? What’s the signal? What can we learn about who we are as humans, or more specifically collectively as filmmakers, or artists in general? Can we use movie barcodes to study different filmmaking generations, directors, or even genres? Is there anything that we as editors should be studying?

When I was a kid we used to have these thing called Magic Eye books. It’s one of those trick your eye games. If you focus your eyes into the distance just right you’ll be able to see an image appear (it's a Zebra).

The point is, data alone is meaningless without researchers following behind to focus that data onto questions that can really inform people about their decision making. In terms of what filmmakers need to learn, we need researchers to ask questions like “what is the normal way movies are made?” Before we can ask ourselves “How can I make my movie unique?” Data gives insight into what humans do by nature, and answers allow future filmmakers to make more deliberate choices based on what we are calling…

The signal in noise of creativity.

Barry Salt and the Origins Of Cinemetrics

An Australian born film historian named Barry Salt dedicated much of his career to answering these exact questions about filmmaking. Barry, who was born in the 1930’s, holds a PhD in theoretical physics. Why the hell he would dump physics to focus on filmmaking I don’t know, but we editors should be thankful he did because he brought a scientific approach to filmmaking - an approach he taught to his film students when he became a film teacher at the Royal College of Art. These are two of his books which outline his conclusions about the choices filmmakers and editors make.

Today we’ll just talk about one paper that Barry wrote called “How They Cut Dialog Scenes” in which he painstakingly measured how editors cut dialog scenes in movies. Barry picked dialog because it’s found in just about every movie, as opposed to a musical number or something, and because dialog between two people is sort of ground zero in terms of what filmmaking focus’s on.

Barry made detailed charts of dozen’s of movies, spanning the decades from the 1930’s all the way to 2014. He tracked L cuts and J cuts. He tracked the number of frames between cuts, and he tracked average shot lengths, and even camera angles used. I want to share with you some of the more interesting tid-bits for editors that I learned while reading this article.

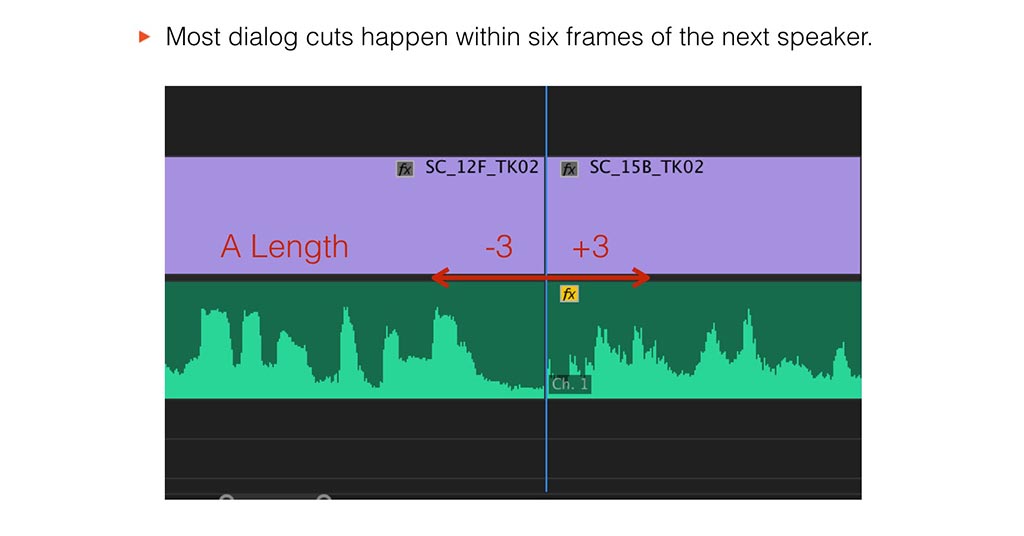

According to Barry, the most common type of edit happens at the end of one person talking and before the next person talking. It’s not in the middle of a word, and it’s not a J or L cut. It’s what we call a straight cut. Most of those cuts happen within 6 frames of when the first person stops talking and when the next person starts.

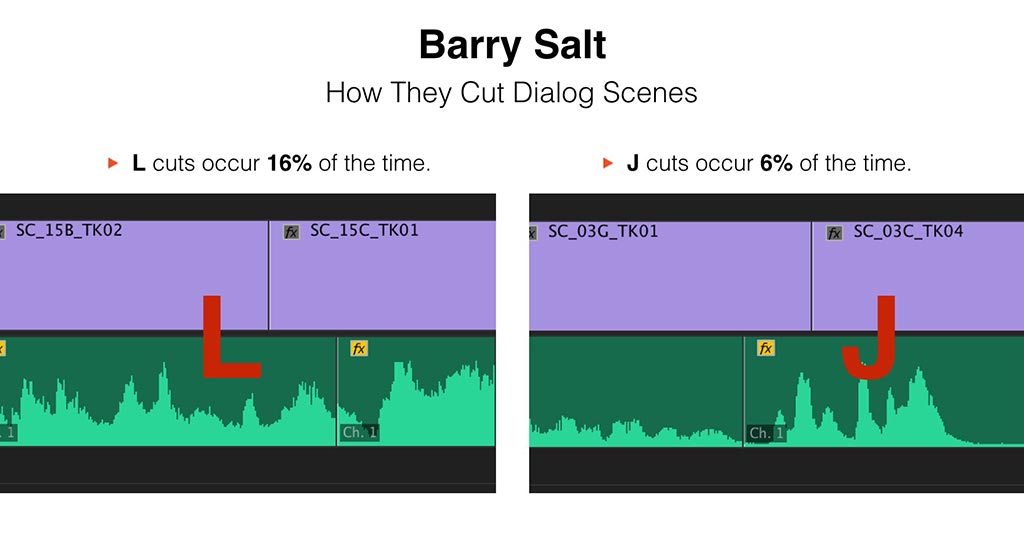

Interestingly, L cuts are more common than J cuts. Barry suspects this is because L cuts allow you to see the recipient listening and absorbing information but also saves time by pulling out the air gap between the lines. That’s absolutely what my editor’s gut instinct has been telling me for years now. But here Barry is explaining it in a way that uses data to measure that belief. Barry isn’t saying that using more L cuts is the “right” way to edit, just that it’s what’s happening most often.

Measuring the Change In Creativity

But there’s more to this J and L cut story then just a percentage of time they are used. And this is where the fun begins. Barry says that in modern film’s J cuts are used almost as often as L cuts. That means this technique has changed over time. Was there a conference of editors that I missed where they all decided it was now ok to use more J cuts in movies? What’s responsible for this change? For that we’re going to need more research. Also interesting is to note that J cuts are typically longer of an overlap than an L cut. But why?

I love this new perspective on editing. Remember how I said earlier that data is just noise until it’s applied against a theory? Well, as a teacher I’m always thinking about better ways to explain editing theory to students.

Instead of telling a student who is learning about J and L cuts something like “editors use L cuts a lot” or “we use L cuts sometimes,” we tell them that historically L cuts are used 16% of the time, and that about 60% of the time you’re likely to cut within six frames of end of someone talking. It feels like a whole new ballgame for me, for the student it will be a much better guiding principle than saying.

Directors and Editors Have A Style That Can Be Measured

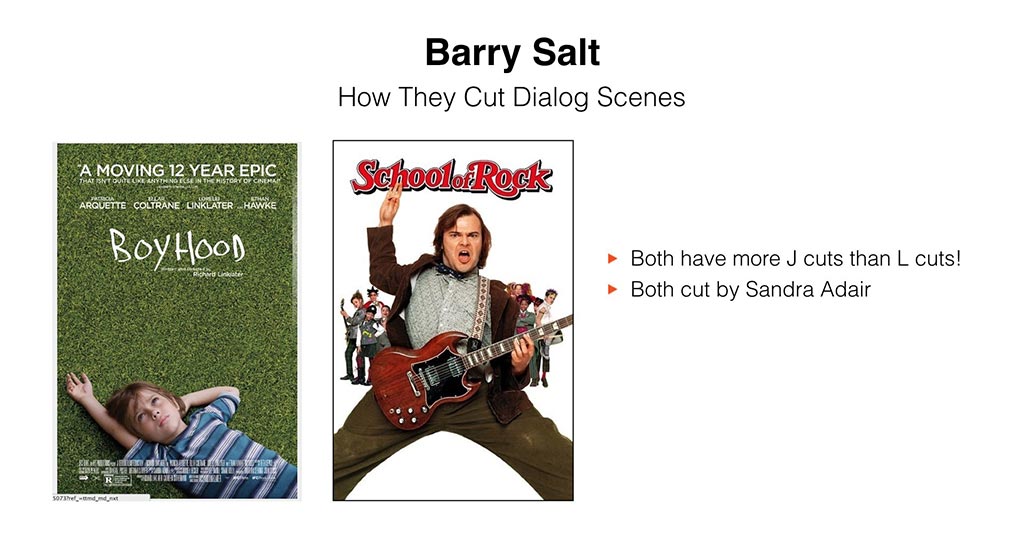

Let’s further show how that creative signal isn’t set in stone. These two films, Boyhood and School of Rock both have more J cuts than L cuts, the opposite of what Barry’s data suggest. Let’s look deeper. Both of these films were edited by the same editor Sandra Adair. Does that mean Sandra made a mistake? Nope. Boyhood was nominated for an Oscar! It just might mean that using more J cuts is Sandra’s style, something she might not even know about herself.

Speaking of style, let’s talk about the two movies Signs and the Sixth Sense. Both were directed by M. Night Shyamalan, but by different editors. However, the two films have a similar amount of frames of silence between the cuts. How can that be? Barry suggests this might be attributed to the director’s style as opposed to the editor’s. We may have learned something about M. Night’s style. Barry notes that most film editors keep the same pacing between movies they work on regardless of the year the film comes out. Editor's have an internal clock.

Finally, we can gain interesting insight through film history with these measurements. For example did you know that modern dialog scenes have more reaction shots in them that those from twenty years ago? Barry attributes this to a vast increase in coverage. There are just more choices now.

Now the fun begins. This is where your mind gets blown...

2 comments

This has been a fascinating journey of discovery for me. The idea of “mapping” creativity in a visual language, that appears measurable mathmatically is just astounding. Love this article!

This is very new and great information that I didn’t came across anywhere. I should get a copy of barry’s book.